Dr. William Judy, founder and president of the SIBR Research Institute, says the manufacturer of a Coenzyme Q10 supplement needs three things in the soft-gel capsule together with the 100 milligrams of dissolved Coenzyme Q10 crystals: A solvent in which the Coenzyme Q10 crystals are dissociated, a stable formulation that will prevent the re-crystallization of the Coenzyme Q10 inside the capsule, and one or more lipids that, ingested together with the Coenzyme Q10, will enhance the absorption of the Coenzyme Q10.

The formulation of the Coenzyme Q10 supplement is of utmost importance. Formulation affects absorption. Absorption affects efficacy. Not all Coenzyme Q10 supplements give the same level of absorption.

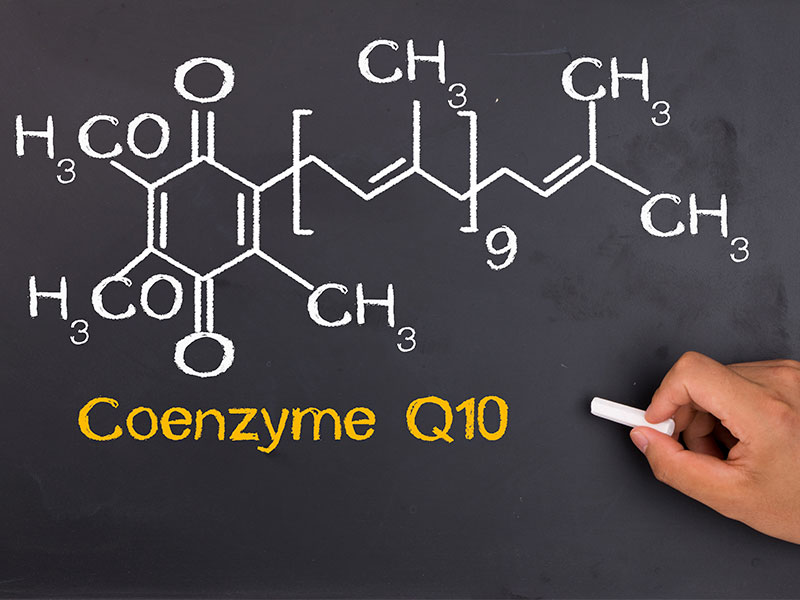

Coenzyme Q10 molecules are fairly large, fat-soluble molecules. Coenzyme Q10 has a six-carbon benzoquinone ring as its head and a ten-unit isoprenoid tail that is strongly hydrophobic. For best absorption, Coenzyme Q10 needs to be ingested together with a meal containing some fat. Despite some claims to the contrary, it is not possible to re-make Coenzyme Q10 into a water-soluble substance. Such a product no longer has the properties of Coenzyme Q10 [Judy 2018].

In its raw form, Coenzyme Q10 is a crystalline substance. The absorption cells in the small intestine cannot absorb crystals, only single molecules of Coenzyme Q10. Therefore, the Coenzyme Q10 crystals need to be dissolved in a suitable solvent in the soft-gel capsule.

Careful formulation of the Coenzyme Q10 supplement adds to the cost of producing the capsules. People shopping for a good Coenzyme Q10 supplement need to keep this in mind. A cheaper supplement may have a beneficial effect, but how to know for sure?

The best thing to do is to check the research results of the individual Coenzyme Q10 supplements. Which supplements have documented research results?

Importance of Coenzyme Q10 supplementation for patients

Coenzyme Q10 supplementation is especially important for the following categories of patients:

Chronic heart failure patients: Adjunctive treatment with 3 times 100 milligrams of Coenzyme Q10 daily improves the symptoms and the survival of chronic heart failure patients [Mortensen 2014].

Patients taking statin medications: Supplementation with Coenzyme Q10 is necessary to replace the endogenous Coenzyme Q10 that is lost because statin medications inhibit not only the bio-synthesis of cholesterol but also the bio-synthesis of Coenzyme Q10 [Okuyama et al 2015]

Patients scheduled for heart surgery: Supplementation with Coenzyme Q10 prior to and following heart surgery helps to preserve heart muscle function to a considerable degree [Judy, Stogsdill & Folkers 1993].

Chronic fatigue syndrome patients: Daily supplementation with Coenzyme Q10 is important for patients with low-energy disorders [Judy & Folkers 1993].

Cancer patients: Daily supplementation of cancer patients with Coenzyme Q10 helps to ameliorate many of the adverse side effects of radiation and chemotherapy [Judy 2018].

Prader-Willi syndrome patients: Daily supplementation of Prader-Willi syndrome children with Coenzyme Q10 helps to normalize development characteristics and to prevent overeating and obesity [Judy 2018].

Patients diagnosed with Gulf War syndrome: Daily supplementation with 100 milligrams of Coenzyme Q10 is associated with statistically significant improvement in general self-rated health, in tests of physical function, and in several symptoms [Golomb 2013].

Coenzyme Q10 supplementation for healthy adults

Daily supplementation of healthy elderly adults with 200 milligrams of Coenzyme Q10 and 200 micrograms of selenium daily was associated with significantly reduced risk of death from heart disease, reduced need for hospitalization and reduced number of days in hospital, and better maintenance of heart function as shown on echocardiograms [Alehagen 2013].

The beneficial effects of the four-year supplementation persisted through a ten-year period [Alehagen 2015]. The researchers attributed the beneficial health effects to a special biological inter-relationship between Coenzyme Q10 and selenium [Alehagen & Aaseth, 2015].

Adults in their 40s and beyond should consider supplementing their diets with a daily Coenzyme Q10 supplement. Research data show that the adults’ bio-synthesis of Coenzyme Q10 declines with increasing age [Kalén 1989].

Adults in their 20s and 30s and beyond who engage in demanding physical work or training that produces extra oxidative stress should consider a Coenzyme Q10 supplement [Diaz-Castro 2012].

Early formulations of Coenzyme Q10

Dr. Judy has been involved in the development and testing of lipid-based ubiquinone Coenzyme Q10 supplements from the beginning back in the early 1980s. Recently, he reviewed the stages of development with me.

The first lipid-based Coenzyme Q10 formulation was the one developed by Dr. Karl Folkers, the chemist and bio-medical researcher who first observed that low blood and tissue levels of Coenzyme Q10 are associated with increased risk of heart disease. Dr. Folkers’ first supplements (1985) were nothing more than powdered Coenzyme Q10 in soybean oil. Even so, they increased blood Coenzyme Q10 levels somewhat.

Then, nearly ten years later (1994), an American firm produced a product that was said to be both water and lipid soluble. This powdered product turned out to contain a wetting agent called polyethylene glycol (PEG), which was later replaced by the wetting agent polysorbate 80.

The third stage of development came two years later (1996) with the introduction of powdered Coenzyme Q10 in rice bran oil.

All of these early formulations had an absorption between 2.4% and 3.0% and a steady-state bio-availability between 2.4 and 3.1 micrograms per milliliter.

Introduction of the crystal-free supplements

The next advance came ten years later (2004-2006) when the powdered Coenzyme Q10 inside the capsules was replaced by dissolved Coenzyme Q10. The tricky part of the formulation process was, of course, keeping the Coenzyme Q10 dissolved inside the sealed capsules.

Coenzyme Q10 is unstable at room temperature. To stay dissolved, Coenzyme Q10 needs temperatures 10 degrees Celsius above normal body temperature, or it needs a special formulation that will keep it dissolved in lipids at room temperature while in storage. The Coenzyme Q10 needs to remain dissolved at body temperature when it is ingested. Otherwise, absorption will suffer.

Also among the contemporary crystal-free formulations, there has been considerable variation. The manufacturers of some of the formulations have succeeded at dissolving the Coenzyme Q10 crystals only to have them re-crystallize inside the soft-gel capsule.

The most successful contemporary formulations have succeeded in raising absorption to 7% – 8% of the 100-milligram capsule and steady-state bioavailability to just above 4 micrograms per milliliter.

Remember, the early formulations using powdered Coenzyme Q10 never got above 3% absorption and 3.1 micrograms per milliliter bioavailability.

Coenzyme Q10 and the future

According to Dr. Judy, there is a theoretical ceiling on the absorption of Coenzyme Q10 at approximately 12% – 15%. Coenzyme Q10 researchers think that the 15% barrier will never be broken [Judy 2018].

Fortunately, the 3 to 8 milligrams that get absorbed from a 100-milligram capsule have been shown to have beneficial health effects in chronic heart failure patients and in ageing healthy adults [Mortensen 2014; Alehagen 2013].

Dr. Judy’s SIBR Institute tests have shown that neither the one-time absorption nor the steady-state bioavailability of the ubiquinol supplements (introduced in 2007) is better than the one-time absorption or steady-state bio-availability of the best lipid-based ubiquinone Coenzyme Q10 supplements [Judy 2018].

Sources

Alehagen, U., Johansson, P., Björnstedt, M., Rosén, A., & Dahlström, U. (2013). Cardiovascular mortality and N-terminal-proBNP reduced after combined selenium and Coenzyme Q10 supplementation: a 5-year prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial among elderly Swedish citizens. International Journal of Cardiology, 167(5), 1860-1866.

Alehagen, U., Aaseth, J., & Johansson, P. (2015). Reduced Cardiovascular Mortality 10 Years after Supplementation with Selenium and Coenzyme Q10 for Four Years: Follow-Up Results of a Prospective Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial in Elderly Citizens. Plos One, 10(12), e0141641.

Díaz-Castro, J., Guisado, R., Kajarabille, N., García, C., Guisado, I. M., de Teresa, C., & Ochoa, J. J. (2012). Coenzyme Q10 supplementation ameliorates inflammatory signaling and oxidative stress associated with strenuous exercise. European Journal of Nutrition, 51(7), 791-799.

Golomb, B. CoQ10 and gulf war illness. Neural Computation 2014 Nov; Vol. 26 (11), pp. 2594-651

Judy, W. V. & Folkers, K. (1993). Management of chronic fatigue syndrome patients with CoQ10. 8th. Intl. Symp. Biomed. and Clin. Aspects of CoQ, 55.

Judy, W. V., Stogsdill, W. W., & Folkers, K. (1993). Myocardial preservation by therapy with Coenzyme Q10 during heart surgery. The Clinical Investigator, 71(8 Suppl), S155-S161.

Judy, W. V. (2018). Private communication.

Kalén A., Appelkvist E.L., & Dallner G. (1989). Age-related changes in the lipid compositions of rat and human tissues. Lipids, 24(7):579–584.

Mortensen, S. A., Rosenfeldt, F., Kumar, A., Dolliner, P., Filipiak, K. J., Pella, D., & Littarru, G. P. (2014). The effect of Coenzyme Q10 on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure: results from Q-SYMBIO: a randomized double-blind trial. JACC. Heart Failure, 2(6), 641-649.

Okuyama, H., Langsjoen, P. H., Hamazaki, T., Ogushi, Y., Hama, R., Kobayashi, T., & Uchino, H. (2015). Statins stimulate atherosclerosis and heart failure: pharmacological mechanisms. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology, 8(2), 189-199.

The information presented in this review article is not intended as medical advice and should not be used as such.

Leave A Comment