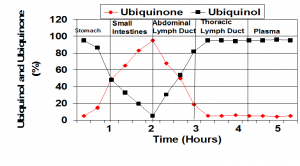

When the ubiquinol supplement enters the stomach and when the capsule opens, the ubiquinol begins to oxidize. In the small intestine, the ubiquinol is converted to almost all ubiquinone. In the absorption cells and in the abdominal lymph ducts, the Coenzyme Q10 is initially almost all in the ubiquinone form. The Coenzyme Q10 enters the blood from the lymph. Thus, it appears that ubiquinol is absorbed as ubiquinone and not as ubiquinol. It is then converted back to ubiquinol before entering the blood. From: Dr. Judy’s presentation at the International Coenzyme Q10 Association symposium in Bologna, Italy, October, 2015.

Q. Good morning, Dr. Judy. Let’s talk about the Coenzyme Q10 research you have done in your career. But, first, do you remember when you first met Dr. Karl Folkers, the grand old man of Coenzyme Q10 research?

A. Good morning. Yes, I met Dr. Folkers in 1968. He had just started the Institute for Bio-Medical Research at UT in Austin. He came to talk to Dr. Les Geddes and Dr. Lee Baker in the Physiology and Biophysics Department at Baylor University Medical School in Houston, Texas. He talked to them about the bio-electrical impedance method for non-invasively measuring cardiac function in heart failure patients.

Dr. Folkers was organizing a group to study the management of congestive heart failure by including Coenzyme Q10 adjunctive treatment in the protocol. I was included in the group because of my experience with non-invasive Trans-thoracic Electrical Impedance, which was used to measure cardiac function with no risk to the patients.

Q. So you were involved in Coenzyme Q10 research from the start?

A. Yes. … <smile> … In those days, we were experimenting with dry powder Coenzyme Q10 supplements. Can you imagine?

Already, by the early 1970s, I was doing animal studies of Coenzyme Q10 transport in the lymph and in the blood at Indiana University Medical School. In Indianapolis. I used dogs. They were not put to sleep, and they were not sacrificed.

Q. So when did you get started on human studies?

A. Ah, in the early 1980s, I was measuring plasma Coenzyme Q10 levels in hypertensive patients. We thought that Coenzyme Q10 supplementation might help protect against cell damage caused by oxidative stress and might reduce blood pressure by uncoupling the contractile element in smooth muscle.

Then – my big breakthrough – we got IRB permission at Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis to do a randomized open-label study and also a randomized double-blind cross-over study using Coenzyme Q10 to manage heart function in congestive heart failure patients.

In 1983, I presented the study results at a conference in Tokyo: Improved cardiac hemodynamics and kinetics in congestive heart failure patients supplemented with Coenzyme Q10. That was excellent.

Q. At that point, you were on your way as a Coenzyme Q10 researcher. What came next?

A. From then on, I was deeply involved. Let’s see. In the mid-1980s, we did lots of studies. It was all new territory back then.

We did so many studies with the ubiquinone form of Coenzyme Q10.

- a study of Coenzyme Q10 to prevent cardiotoxicity in Adriamycin-treated lung cancer patients

- a long-term study of the management of congestive heart failure with Coenzyme Q10 (30-year study)

- a study of Coenzyme Q10 effects in congestive heart failure patients with cancers

- a study of Coenzyme Q10 stabilization of cardiac function in heart transplant patients

- a study of the prevention of hyper-glycemia in early-onset Type 2 diabetic patients

We also looked at Coenzyme Q10’s effect on the stabilization of cardiac membranes and the reduction of abnormal cardiac electrical function.

Even with the dry powder Coenzyme Q10 supplements, we could see the improvement in the patients. We knew we were on the right track.

What we needed, of course, was a good Coenzyme Q10 supplement with better absorption. Coenzyme Q10 molecules are difficult to absorb. The supplement’s formulation has to be right.

Q. You were off and running, so to speak.

A. In about 1985, I got some unexpected foundation funding, and then I was busy doing Coenzyme Q10 research for the rest of the 1980s. It was an exciting time. Let’s see. We had some good study results, again with the ubiquinone Coenzyme Q10.

- Coenzyme Q10 improved cardiac function in high-risk patients undergoing cardiac vascular by-pass surgery or other heart surgery.

- Coenzyme Q10 lowered blood glucose in in refractory Type 2 diabetic patients but had no effect on glucose control in early-onset Type II diabetics.

- Coenzyme Q10 induced remission of cancers in congestive heart failure patients.

- Coenzyme Q10 reduced cardiac arrhythmias in congestive heart failure patients.

- Coenzyme Q10 had beneficial effects on heart transplant patients.

And — this was important to see — the withdrawal of Coenzyme Q10 supplementation induced a clinical relapse in congestive heart failure patients and a return of more severe heart failure. That result made us sit up and take notice.

Then, in 1987, we started testing the absorption and bioavailability in healthy study participants of Dr. Folkers’ new Coenzyme-Q10-in-soybean-oil supplement.

Q. But it was still the dry powder Coenzyme Q10? Just mixed with soybean oil in a capsule instead of pressed into a tablet?

Dr. Karl Folkers (left), founder of the Institute for Bio-Medical Research and initiator and supporter of much Coenzyme Q10 clinical research, pictured here with Dr. Svend Aage Mortensen, lead researcher on the Q-Symbio study of Coenzyme Q10 adjunctive treatment of chronic heart failure patients.

A. Yes … <smile> … still a long way from today’s supplements.

What came next was that I retired from the Indiana University Medical School and moved to Bradenton, Florida. I didn’t really do any Coenzyme Q10 research until 1995 when I founded the SIBR Research Institute.

Dr. Folkers came to see me and tried to convince me that I should start doing research with Coenzyme Q10 again. He offered to help me. He funded the SIBR Research laboratory and some Coenzyme Q10 studies.

That is when we – SIBR Research – started doing heavy-duty absorption and bioavailability studies of many different formulations of Coenzyme Q10 supplements for many different companies, trying to find out what worked best.

Somewhere in there, mid-1990s, the industry began to use the new soft-gel capsules.

In the late-1990s, in addition to absorption and bioavailability studies, I was involved in more studies of Coenzyme Q10 adjunctive treatment:

- prostate cancer patients

- chronic fatigue syndrome patients

- Prader Willi syndrome patients – infants and small children

Q. So, now, in our chronology, we are entering the 21stcentury. What were you working on in the 2000s?

A. More absorption and bioavailability testing for various companies that I can’t name, for contractual reasons. And I was able to report the twenty-year follow-up life-or-death review of the congestive heart failure patients taking Coenzyme Q10.

This study is now thirty years old. It is the oldest ongoing Coenzyme Q10 study in the world. When we started, we knew that all congestive heart failure patients on conventional therapy alone were dead in eight years’ time.

But, at eight years in our study, almost 50% of the patients treated with an adjunctive Coenzyme Q10 treatment — in additional to conventional therapy — were still living. At 20 years, 24% were still living. Today, we still have two patients in the Coenzyme Q10 treatment group living.

Q. Then, around the year 2000, the big new research area was Coenzyme Q10 treatment for statin-induced muscle fatigue and weakness, isn’t that right?

A. Yes, by then we had known for some time that the statin medications, in blocking the synthesis of cholesterol, were also lowering the body’s production of Coenzyme Q10 in various age groups.

The reduced plasma Coenzyme Q10 levels were associated with low energy, muscle pain, muscle cramps, and a poor exercise tolerance in the statin-treated patients. We knew that that could not be a good thing in the long run.

Patients taking statin medications need extra Coenzyme Q10. It is as simple as that. And there are a lot of people taking statin medications these days.

Q. Then, 2006, the ubiquinol supplements came onto the market in the United States. Had you seen that coming?

A. Yes, we had. SIBR research tested the absorption and bioavailability of the ubiquinol product as early as 2003. It was called bio-active Coenzyme Q10 at that time.

We did not find that it had an absorption or bioavailability any better than a good lipid-based softgel Coenzyme Q10 formulation.

Honestly, ubiquinol supplements did not seem like a good idea to me. I knew that ubiquinol, the reduced form of Coenzyme Q10, is very unstable and very difficult to work with.

If ubiquinol gets exposed to room air, it will oxidize. It will revert to the ubiquinone form, the more stable form, the form that we had been testing since the early 1980s.

At SIBR Research, we started testing the ubiquinol products on the market. We often found that some or all of the ubiquinol in the capsules had oxidized to ubiquinone – even before the capsule had been swallowed. This was especially true in products that contained antioxidants and vitamins.

And – an important point – we found that the ubiquinol in capsules was oxidized to ubiquinone when it reached the gastric juices in the stomach.

By 2009 or so, our lab studies were showing consistently that the ubiquinol in supplements is converted to ubiquinone in the stomach and intestines before absorption.

At SIBR Research, we were puzzled: why would people pay good money for an unstable ubiquinol supplement that would be converted to ubiquinone anyway?

Dr. Judy spoke about the absorption and transfer of Coenzyme Q10 at the International Coenzyme Q10 Association symposium in Bologna, Italy, October, 2015.

Q. And then there was the red flag of misleading marketing claims for ubiquinol, isn’t that right? That bothered you, didn’t it?

A. You are correct. It seemed to me that the ubiquinol product was introduced with lots of marketing claims that were not backed up by good solid research like the research that was done with ubiquinone Coenzyme Q10 supplements in the Q-Symbio study and the KiSel-10 study, for example.

And the absorption comparisons that were used to support the marketing claims for ubiquinol, they seemed to be contrived.

My SIBR Research colleagues and I wrote an article called “Coenzyme Q10: Facts or Fabrications.” We tried to set the record straight, based on what is known from research instead of just from marketing claims.

Q. Thank you, Dr. Judy, for this little summary of Coenzyme Q10 research history. With your permission, I will use one of the illustrations from your 2015 presentation at the International Coenzyme Q10 Association symposium.

A. Thank you. Yes, please, go ahead and use the illustration. It sums up the results of our research on absorption.

Leave A Comment